Unlocking Stories Through Art: The Complete Guide to Narrative Art

Narrative art has the remarkable power to bring stories to life, capturing human experiences, emotions, and history in vivid visual detail. Through the ages, artists have used this form of art to share everything from mythic tales to everyday scenes, influencing how we understand cultures and ourselves. On this page, we'll journey through its fascinating evolution, uncovering the techniques artists use, exploring its roles within society, and highlighting key moments and figures who have shaped this storytelling medium.

A Quick Look: The Essence of Narrative Art

Narrative art, quite simply, is about telling stories through pictures. It's one of the oldest ways humans have expressed themselves, stretching from ancient cave paintings all the way to today's digital wonders. This report dives into what narrative art is, how it has changed over time, and the many ways it touches our lives.

At its heart, narrative art always involves storytelling.1 However, this can range from clear, step-by-step pictures to artworks that just "imply an association," showing how our idea of what a 'narrative' even is has grown.3

Key ingredients usually include showing (or hinting at) a sequence of events, developing characters, stirring emotions, and using recognizable images, though exactly what it all means is often up to the viewer.4 Narrative art is different from abstract art because it uses identifiable subjects to tell its tale. It also stands apart from decorative art, which focuses more on beauty than on deep, metaphorical storytelling. While allegorical art tells stories with hidden symbolic meanings, it's actually a special kind of narrative art.7

The historical journey of narrative art shows a consistent aim: to communicate, save experiences, and create meaning. Yet, what stories are told, how they look, and their role in society have shifted with cultural, technological, and ideological changes.10

Think of the sacred scenes in ancient Egyptian tombs,12 the power statements in Roman carvings like Trajan's Column,2 the teaching power of medieval illuminated books,14 or the human-focused stories in Renaissance frescoes.15 Each served a different purpose.

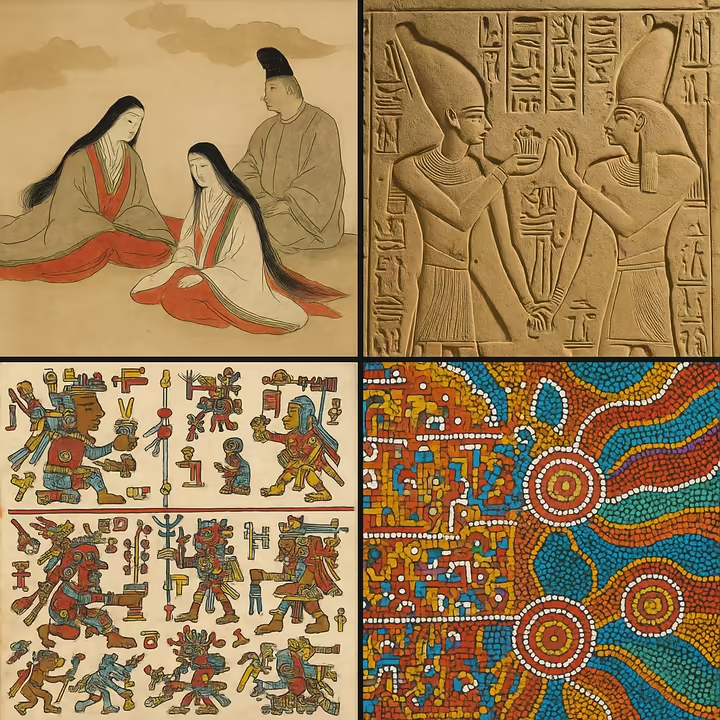

Around the world, traditions like Japanese emakimono scrolls,16 Mexican codices,17 African storytelling fabrics,18 and Indigenous Australian Dreamtime paintings19 show the amazing variety in visual storytelling. Local beliefs and materials deeply influence how these stories look and what they mean, and understanding them often requires knowing the culture's unique symbols and customs.20

Visual storytellers use many techniques, like how they arrange elements (composition), show events in order (sequential imagery like monoscenic or continuous scenes), use symbols, and portray characters and feelings.2 The medium itself, whether it's painting, sculpture, photography, comics, film, or interactive digital art, shapes what's possible, with new technologies allowing for exciting new levels of interaction and viewer choice.23

Artists like Norman Rockwell, Faith Ringgold, and Kara Walker offer different ways of telling American stories, often challenging old forms and ideas.25 Figuring out what narrative art means is a lively exchange between the art, the viewer's own background, and how experts like Panofsky (iconology) or Barthes (semiotics) suggest we look at art.28

Today, narrative art increasingly gives voice to marginalized groups, shares personal stories, and tackles urgent social, political, and environmental issues, often using new media to create immersive experiences.30 In education, it's a vital tool for teaching visual literacy, critical thinking, empathy, and cultural understanding.32 Ultimately, narrative art continues to be a powerful way to reflect, shape, and question our human experience across all cultures and throughout time.

What Exactly Is Narrative Art? Understanding the Basics

Defining the Craft: Scholarly Perspectives

At its core, narrative art is simply art that tells a story. This broad umbrella covers works that capture a single moment within a larger tale or present a series of events unfolding over time.2

StudySmarter puts it concisely: narrative art is "visual storytelling that conveys a story or an action through imagery, often featuring characters, settings, and events, enabling viewers to grasp plot or thematic elements without written text".1 This definition highlights the power of visuals to communicate complex ideas.

The way we understand narrative art has evolved. The Mulvane Art Museum notes that while "narrative art has held various meanings throughout history," today, art is considered narrative if it "tell[s] a story or impl[ies] an association".3 This modern view is echoed by the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA), which simply defines narrative art as "artwork that tells a story".6

The NMWA adds that artists provide visual clues, like settings and symbols, to help us follow these narratives.6 Similarly, Jerwood Visual Arts describes it as a "form of visual art that tells a story or conveys a message through a sequence of images" using various media like painting, sculpture, photography, and digital art.4 The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art agrees, stating that narrative art is "created to represent stories through images," identifying storytelling, inspired by religion, myth, history, literature, or events, as a key motivation for much of the world's art.11

While these definitions all center on "storytelling," they differ slightly in how obvious the story needs to be. Some definitions focus on direct storytelling, while others, by including the idea of "implying an association,"3 embrace a wider range of narrative possibilities.

This nuanced understanding suggests a shift from perhaps stricter historical definitions to a more inclusive modern view. This flexibility allows us to include works that might be more abstract or suggestive, without a clear, linear plot, yet still capable of sparking a story or a series of connections in our minds. Such an evolution likely mirrors broader cultural changes in how we understand narrative itself, moving beyond strictly straightforward forms to embrace more ambiguous and viewer-dependent ways of telling stories.

Key Traits: What Makes Art Narrative?

Several key characteristics help us identify narrative art. A primary feature is often the presence of sequential imagery or an implied sequence, suggesting a timeline or how events unfold.4 This can be achieved through multiple panels, like in comics, or by how elements are arranged within a single picture.3

OnlineArtLessons.com emphasizes that narrative art must be sequential, meaning we should be able to infer a sequence of events, past, present, and future, even if not all are explicitly shown.5 This ability to infer is a crucial difference from art that simply shows something without telling a story. So, "sequentiality" isn't always a literal series of images; it can also be a mental act, where we piece together clues within a single work, often relying on our cultural knowledge and imagination. This active role of the viewer is key to how we receive and interpret stories.

The visual development of characters and the conveyance of emotion are also central to narrative art.4 Artists use various visual cues, like setting, subject matter, symbols, point of view, and perspective, to develop characters and communicate their feelings, thereby drawing us into the story.6 The artwork should allow us to grasp the plot progression, whether this progression is obvious or subtly suggested.1

Narrative art is typically representational, meaning the images, elements, and symbols used are recognizable from the real world, even when depicting fantasy or myths.5 However, it's important to remember that not all representational art tells a story. A static portrait, like Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, shows a person but doesn't inherently tell a story. In contrast, a work like Johannes Vermeer's The Milkmaid, while a portrait, implies a narrative through its depiction of action and context.5 Furthermore, a narrative artwork will generally evoke an emotion in the viewer, adding to its storytelling impact.5

Finally, narrative art often leaves room for viewer interpretation; it doesn't always spell everything out.3 This openness invites us, the audience, to actively engage with the artwork, using our own experiences and understanding to complete or interpret the story being told.

Setting It Apart: Narrative Art vs. Other Styles

Narrative vs. Abstract Art

Narrative art and abstract art sit at different ends of the artistic spectrum. Narrative art, by its very nature, aims to tell a story using recognizable subjects and depicting events, whether real or imagined.7 Its main job is to show a sequence of actions or a key moment in a larger story.

In contrast, abstract art deliberately moves away from, or completely abandons, showing objective reality.7 Instead of focusing on recognizable figures or scenes, abstract art uses formal elements like color, line, shape, and texture to evoke emotions, explore beauty, or convey personal experiences.38 Humanities LibreTexts points out that while narrative art uses identifiable content to tell its story, the meaning in abstract art is often personal and can be hard to pin down without extra information, like a statement from the artist.7 When we look at abstract art, we typically focus on its visual impact and the feelings or sensations it sparks, rather than trying to figure out a plot.

Narrative vs. Decorative Art

The line between narrative and decorative art often comes down to their main purpose and perceived depth. Decorative arts are frequently defined by their goal to beautify objects or spaces, often blending function with visual appeal.39 Fine arts, a category that traditionally includes narrative painting, are generally seen as producing items valued "solely for their aesthetic quality and capacity to stimulate the intellect".39

The Illustration Art blog suggests a deeper distinction, arguing that narrative art has "vast metaphoric power" and comes from "deep conviction," uniting surface beauty with profound meaning to share something "eternal and mysterious" with us.8 Decorative art, in this view, focuses on "surface effects," aiming "to please with harmony and theatrics," and is mainly symbolic rather than metaphorical, thus lacking the same deep impact.8

This perspective suggests that narrative art tries to engage us intellectually and emotionally through storytelling and metaphor, while decorative art focuses on aesthetic pleasure and embellishment, sometimes for practical or commercial reasons. However, this distinction isn't always clear-cut and can be subjective. Some argue that all art has narrative potential, and that design and decoration are fundamental aspects of visual art, challenging a strict separation.8 The debate highlights the fluid boundaries and potential overlaps, where "depth" and "purpose" can be matters of interpretation and cultural value.

Narrative vs. Allegorical Art

Allegorical art has a special place within the broader world of narrative art. It's known for its use of "veiled language" (from the Latin allegoria) to tell a story that carries a "hidden significance" or a "deeper message".9 Allegories use symbolic figures, actions, and imagery to express complex abstract ideas like love, life, death, virtue, or justice.9

While all allegories inherently tell a story, a basic feature of narrative art, their main distinguishing mark is this deliberate layering of symbolic meaning. The story structure in allegorical art serves as a way to deliver a specific, often moral, philosophical, or political message that goes beyond the literal events shown.9 M.S. Rau Antiques suggests that allegory is an effective tool within the larger realm of storytelling.9

Therefore, allegorical art can be seen as a specialized type of narrative art. Not all narrative art is allegorical, as many stories are told for their own sake or for other reasons without a hidden symbolic layer. However, all allegorical art is, by its nature, narrative, because it relies on a sequence of events, characters, and settings to unfold its symbolic meaning. It's this "veiled language" and the intent to communicate a specific abstract idea that set allegorical art apart.

The 'Why' of Storytelling: Purpose and Evolution

The fundamental reason for narrative art, a constant thread throughout its long history, is to communicate and create meaning. This includes preserving experiences, passing down knowledge, and helping people and societies make sense of the world.10 It aims to teach, inspire, inform, keep memories and cultural heritage alive, and help us understand diverse human experiences.6

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art highlights its profound role in shaping beliefs, sharing societal values, sparking imagination, and building communities.11 George Lucas himself stated that narrative art "tells the story of a society, most importantly, what the common beliefs are that hold it together”.11

While this core communicative job has stayed the same, the specific purposes, subjects, and styles of narrative art have changed dramatically with shifting cultural, social, political, and technological landscapes. In prehistoric times, early forms like cave paintings likely served to record experiences, help with rituals (perhaps for successful hunts), and document daily life and beliefs.3 Ancient civilizations like Egypt used narrative reliefs and tomb murals to sustain life, document royal achievements, and ensure religious ceremonies were properly performed.3 During the early Christian era, narrative art, especially stained glass windows and manuscript illuminations, became a powerful tool for religious teaching, visually sharing Bible stories with a largely illiterate population. 3

Later periods saw narrative art used to depict important historical events and, especially in the 20th century with movements like Social Realism, to comment on contemporary culture and society.3 In 19th-century America, for instance, narrative art helped shape a growing national identity.45 The arrival of Modernism brought a big shift, often rejecting or radically changing traditional narrative forms, with more emphasis on personal expression, subjective experience, and social critique.3 Contemporary narrative art continues this path, frequently used for activism, to challenge dominant stories, give voice to marginalized communities, and explore complex issues of identity, politics, and the environment.4

Our scholarly understanding of narrative art's purpose has also evolved. Initially, it might have been seen mainly for its documentary or teaching functions. However, modern views, like those from Artsology.com, trace a more nuanced evolution: from recording basic experiences and beliefs to capturing personal and emotional truths within historical accounts, reflecting multiple viewpoints, embracing ambiguity, and critically, providing a platform for voices that have been historically silenced.10

This journey shows a diversification and democratization of narrative purpose. The shift from grand historical or mythological stories, often commissioned by the powerful, to more personal, introspective, or critical narratives created by a wider range of artists marks a significant evolution in what stories are considered important and whose perspectives are valued. This broadening scope highlights narrative art's enduring ability not only to reflect but also to shape and question human experience.

A Journey Through Time: The History of Narrative Art

In the Beginning: Origins and Early Expressions

Prehistoric Cave Paintings

The story of narrative art begins with some of humanity's earliest artistic creations: prehistoric cave paintings. These ancient artworks, found in places like Lascaux in France, Altamira in Spain, and Sulawesi in Indonesia, date back over 40,000 years.42 The images mostly feature animals, hunting scenes, and mysterious human-animal figures.10

Scholars have many theories about their purpose, suggesting they were used for shamanistic rituals, sympathetic magic for successful hunts, recording daily life, or early forms of symbolic storytelling to preserve experiences and pass down knowledge.10

However, whether these paintings are explicitly "narrative" is still debated. While these images undoubtedly held significant meaning for their creators, some sources, like Britannica, note that clear narrative elements, especially those involving sequential storytelling, are rare in much cave art.42 The focus often seems to be on individual animals or symbolic compositions rather than a linear sequence of events. This view contrasts with interpretations from Artsology, which see these works as foundational examples of symbolic storytelling.10

It's plausible that the "story" in cave paintings was less about a chronological sequence and more about capturing an essential belief, a significant event, or a relationship with the natural and spiritual world, a broader, more symbolic form of narrative. The power of the imagery is undeniable, but its precise narrative structure, by modern definitions, remains elusive and open to interpretation.

Ancient Egyptian Reliefs and Tomb Murals

Ancient Egyptian art offers clearer examples of early narrative forms, especially in reliefs and tomb murals. These elaborate decorations served deep religious and commemorative purposes, believed to ensure eternal life for the deceased, magically guarantee important ceremonies, and meticulously record the achievements of royalty and the elite.12 The tradition of mural decoration is evident from the 3rd Dynasty, with the tomb of Hesire at Ṣaqqārah featuring murals of funerary items and finely carved low reliefs.12

Egyptian artists used sophisticated techniques, painting on mud brick or lower-quality stone, and carving reliefs into good quality stone, often painting the finished carvings.12 The layout involved red guidelines and black outlines, with mineral-based tempera paints providing color. Hieroglyphs frequently accompanied the visual scenes, creating a close link between text and image that enriched the narrative.3

Notable examples span Egyptian history, from Old Kingdom reliefs in King Neuserre's sun temple and private tombs like those of Ptahhotep and Ti, to New Kingdom masterpieces like the carvings in Hatshepsut’s temple at Dayr al-Baḥrī and Seti I's refined reliefs at Karnak and Abydos.12 It's crucial to remember that many of these intricate narrative works weren't meant for living eyes; their main purpose was to benefit a divine recipient or the deceased in the afterlife, ensuring their safe passage and continued existence.43

Milestones in Art History: Key Periods

Classical Antiquity (Greece & Rome)

Narrative art truly blossomed in Classical Antiquity, with unique developments in both Greece and Rome.

Greek Pottery: Greek vase painting, using techniques like black-figure and red-figure, is a treasure trove of narrative art. These vessels, from large amphorae to smaller cups, were adorned with scenes from mythology, epic poems, and daily life, turning everyday objects into storytelling media.3 Artists developed clever narrative techniques to tell complex stories on the curved surfaces of vases. These included monoscenic narrative (showing a single, important moment), continuous narrative (showing multiple story phases in one unbroken band, often with the main character repeated), synoptic narrative (combining several moments or characters into one frame), and cyclic narrative (a series of separate scenes illustrating a longer story, like a comic book).50 Major museums, like the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, showcase many examples.52

Roman Reliefs: The Roman Empire used narrative relief sculpture on a massive scale, often for public display and imperial propaganda.

Trajan’s Column (Rome, 113 CE) is a prime example. It features a continuous spiral frieze over 600 feet long that meticulously recounts Emperor Trajan's military campaigns in Dacia.2 The relief uses perspective and detailed depictions of battles, sieges, and Roman military operations, serving as both a historical record and a testament to Roman power and Trajan's leadership.

The Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace, Rome, dedicated 9 BCE) is another key monument. It's adorned with reliefs including mythological scenes, allegorical figures, and a famous processional frieze showing Augustus, his family, and various dignitaries.13 This monument skillfully blends Greek artistic influences with Roman historical and ideological content, spreading imperial iconography and presenting the emperor as a central figure in Rome's destiny.54

These Roman narrative reliefs weren't just documentary; they strategically crafted and spread specific political and ideological messages about power, virtue, and the emperor's divine favor. They shaped public perception and solidified imperial authority, showing how visual narratives can be powerful tools of state communication.

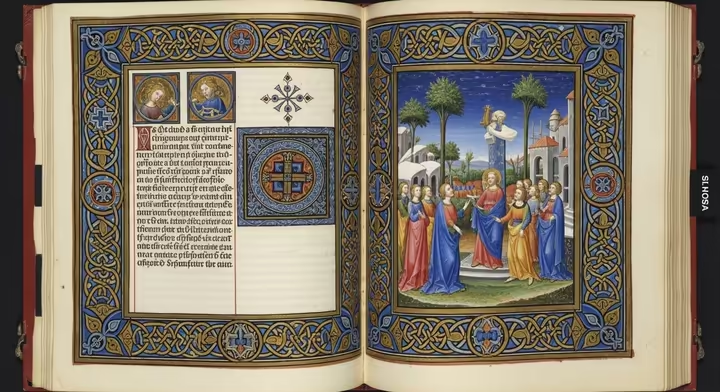

Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts and Tapestries

During the Medieval period, narrative art thrived in forms that served religious, educational, and commemorative purposes.

Illuminated Manuscripts: Before printing, books were precious, handmade items. Illuminated manuscripts, painstakingly created in monasteries and later in city workshops, were central to this tradition.14 "Illumination" refers to decorating these manuscripts with gold, silver, and vibrant colors.55 Decorations included ornate initial letters, elaborate borders, and, most importantly for narrative, miniatures – small, detailed paintings illustrating the text.14

Most illuminated texts were religious, like Bibles, Books of Hours (personal prayer books), Gospels, and Psalters, where images brought sacred stories to life for both literate and illiterate audiences.14 Pope Gregory the Great famously called religious images the "bible of the illiterate," highlighting their teaching power.44 Secular texts, like chronicles, genealogies, romances, and bestiaries (animal stories with moral lessons), were also illuminated.14 The margins often contained whimsical drawings or comments, offering glimpses into medieval humor and society.14

Tapestries: Large-scale textile art, especially tapestries, was another important medium for narrative in the Middle Ages. The Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1070s), though technically an embroidery, is the most famous example.2 This remarkable work, nearly 70 meters long, shows the events leading up to and including the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, ending with the Battle of Hastings.2

It uses a continuous narrative, with scenes flowing one after another, often with Latin text identifying characters and events. The Bayeux Tapestry is an invaluable historical document, providing visual information on medieval costume, ships, military gear, and battle tactics.56 Scholars still debate its patronage (likely Bishop Odo of Bayeux) and purpose. Sarah Bulger, for instance, argues that the Tapestry, with its fables and humorous border details, might have been a teaching tool for young nobles, not just political propaganda or religious decoration.57

Renaissance Cycles and Frescoes

The Renaissance was a golden age for narrative art, especially in Italy. It was fueled by a renewed interest in classical antiquity, humanism, and advances in artistic techniques.4 Fresco painting, where pigments are applied to wet plaster, became a popular medium for large-scale narrative cycles on the walls of churches, chapels, and palaces.58

Artists mastered techniques like linear perspective to create convincing illusions of depth and chiaroscuro (strong light/dark contrasts) to model forms and create drama, boosting the storytelling power of their images.4

Giotto di Bondone is considered a key figure in this development. His fresco cycle in the Scrovegni Chapel (Arena Chapel) in Padua (c. 1305) depicts scenes from the lives of the Virgin Mary and Christ with unprecedented emotional intensity, psychological realism, and a new understanding of space.15 Giotto's ability to show human emotion through gesture and expression, and to place figures in believable, three-dimensional settings, was a break from the flatter, more symbolic medieval style and paved the way for future Renaissance painters.15 The Padua fresco cycles as a whole show a century of continuous development in mural painting, with evolving approaches to space and narrative complexity.15

Later Renaissance masters built on these foundations. Michelangelo Buonarroti's frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican (1508-1512) are one of Western art's most ambitious narrative projects, showing iconic scenes from Genesis with heroic figures and dynamic compositions.4 Raphael Sanzio's frescoes in the Vatican Stanze (Rooms), like The School of Athens (1509-1511), while not strictly narrative like biblical cycles, tell stories about philosophy, theology, and poetry through complex allegories and idealized figures.58 These artists, and many others, used narrative cycles to explore profound sacred and secular themes, celebrate human achievement, and reflect the intellectual and cultural vibes of the Renaissance.

Baroque Period

The Baroque period (roughly 1600-1750) filled narrative art with heightened drama, dynamism, and emotional intensity.59 Artists of this era aimed to engage viewers directly and viscerally, often using theatrical compositions, rich details, and masterful chiaroscuro (a powerful form of contrast in art) to create powerful visual experiences.59

Narrative subjects, especially religious and mythological ones, were rendered with unparalleled depth and passion, aiming to evoke strong feelings of awe, piety, ecstasy, or even terror.59 Painters like Caravaggio revolutionized religious narrative with stark realism and dramatic lighting, bringing biblical scenes to life with unprecedented immediacy (e.g., The Calling of St. Matthew).46 Sculptors like Gian Lorenzo Bernini captured peak moments of action and emotion in marble (e.g., The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa).

Artists such as Peter Paul Rubens depicted dynamic mythological and allegorical scenes filled with energy and sensuality. Meanwhile, Rembrandt van Rijn, though also known for introspective portraits, created powerful biblical narratives imbued with psychological depth.59 In Spain, Diego Velázquez brought profound realism and complexity to royal portraits and historical scenes that often carried narrative undertones.59 The grandeur of Baroque art, in painting, sculpture, or architecture, frequently served the agendas of the Catholic Counter-Reformation and powerful monarchies, using narrative to inspire faith, assert authority, and overwhelm the senses.

19th-Century Illustration and Painting

The 19th century saw narrative art diversify, reflecting significant social, political, and cultural changes. In America, it played a crucial role in shaping the young nation's identity and reflecting its tastes, aspirations, and contradictions.45

Historical paintings aimed to build national pride by depicting figures like George Washington and key past events.45 Genre scenes, popularized by artists like William Sidney Mount, focused on ordinary people's lives, often in rural settings, conveying values of farm work, family, faith, and commerce.45 These seemingly simple depictions often held symbolic messages about contemporary issues, easily understood by 19th-century audiences.45

Furthermore, some narrative art began to address growing awareness of economic and social divisions, and the harsh realities faced by marginalized groups, including enslaved African Americans (e.g., Eastman Johnson's Negro Life at the South) and Native Americans. These works sometimes reinforced, and at other times challenged, prevailing societal biases.45 John Rogers' popular sculptures, like The Fugitive’s Story, directly supported the abolitionist cause.45

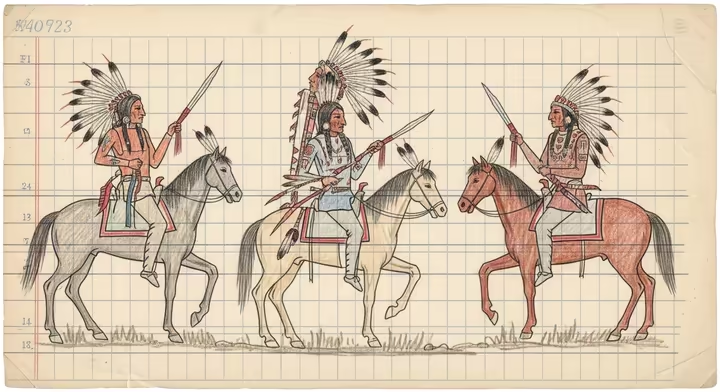

A distinct form of narrative art emerged among Plains Native American communities, often called "ledger art".61 This tradition evolved from earlier practices of warrior artists recording visionary experiences, battle successes, and important communal events on buffalo hides, robes, and tipis.61 With new materials like paper, pencils, and crayons becoming available through trade in the 19th century, Plains artists adapted their narrative practices.61

During the turbulent Reservation Era (1870–1920), as U.S. government policies encroached on Native identities and traditions, these pictorial drawings became a vital way to address cultural upheaval, document personal experiences, and preserve history.61 Artists like Bear's Heart (Southern Cheyenne) and Zo-tom (Kiowa) created powerful visual records of this period.61

Modernism (Impact on Narrative)

The arrival of Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought a profound rethinking of art's purpose and forms, significantly affecting traditional approaches to narrative.3 Modernism was marked by a rejection of academic rules and a turn towards personal vision, subjective experience, fragmentation, and an exploration of art's fundamental elements.62

In literature, Modernist writers like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf experimented with techniques like stream-of-consciousness and non-linear narratives to capture modern life's complexities.62 This shifted focus from straightforward plots to internalized, often ambiguous, narrative experiences.

In visual arts, movements like Cubism, Expressionism, and Surrealism radically changed representation. Cubists like Picasso fragmented subjects and showed them from multiple viewpoints at once, challenging traditional perspective.65 Expressionists like Edvard Munch focused on conveying intense emotions, often distorting form and color.66 Surrealists, influenced by Freud, delved into the unconscious, dreams, and the irrational, creating bizarre narrative juxtapositions.66

Some see Modernism as rejecting narrative entirely in favor of pure abstraction and "truth to materials."3 However, it's more accurate to say Modernism radically transformed narrative expression. Instead of coherent, linear stories, Modernist art often presented fragmented, subjective, or open-ended narratives. The "story" frequently moved inward, reflecting a changed understanding of reality and the self in a rapidly changing world.63

20th-Century Comics and Graphic Novels

The 20th century saw comics and graphic novels rise as a significant and distinct form of narrative art.69 Originating from newspaper comic strips, the medium developed through pioneers like Rodolphe Töpffer, Lynd Ward, and later, Will Eisner. Eisner's 1978 work, A Contract with God, is widely credited with popularizing "graphic novel" and showing the medium's potential for mature storytelling.69 Harvey Kurtzman also contributed with works like Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book (1959).70

The latter half of the 20th century saw graphic narratives gain new literary and artistic respect. Seminal works like Art Spiegelman's Maus (1980-1991), a Pulitzer Prize-winning Holocaust account, showcased the medium's power.69 Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen (1986-1987) and Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns (1986) redefined superhero conventions with darker themes and complex structures.69 Neil Gaiman's Sandman series (1989-1996) further expanded the medium's boundaries.69

These works solidified the graphic novel as a legitimate art form capable of telling diverse, nuanced stories, distinct from simpler comic books. The term "graphic novel" gained currency for these more ambitious, often creator-owned, and mature works that used the unique interplay of text and sequential images for rich narrative experiences.70

The World Around Us: How Context Shapes Narrative Art

The subjects, styles, and functions of narrative art throughout history have been deeply shaped by the social, political, religious, and technological contexts of their time.46 Art doesn't exist in a bubble; it's a product of its environment and, in turn, reflects and influences that environment.

Political turmoil, for instance, has often inspired artists. Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (1830) is an iconic response to France's July Revolution, while Francisco Goya's The Third of May 1808 (1814) harrowingly narrates atrocities during Napoleon's invasion of Spain.46 Similarly, war and peace leave distinct marks. Pablo Picasso's Guernica (1937) is a monumental anti-war statement about the Spanish Civil War bombing. Conversely, the Impressionist movement captured scenes of leisure during a period of relative peace and industrial growth.46

Religious beliefs have been a dominant force in shaping narrative art for millennia. Medieval Christian art, from stained-glass windows to illuminated manuscripts, primarily taught biblical stories and reinforced faith.44 The 16th-century Protestant Reformation led to shifts in religious art in some regions, favoring simpler depictions aligned with personal devotion.46

Class structures and patronage have also dictated narrative art's content and purpose. During the Renaissance, wealthy patrons like the Medici family commissioned works glorifying their power.46 In contrast, 19th-century Realism, seen in Gustave Courbet's The Stone Breakers, brought working-class lives into narrative art, challenging elite-dominated narratives.46

Technological advancements have consistently provided new media for narrative expression and fundamentally altered storytelling. The 15th-century printing press enabled mass production of illustrated narratives.14 19th-century photography introduced new possibilities for documentary and artistic narrative.74 20th-century film and animation brought motion and sound.75

Most recently, digital technologies, internet, social media, VR, AR, have revolutionized narrative art.23 These new media foster interactivity, non-linearity, and participatory experiences, where the viewer can become a co-creator. This marks a significant shift from passive reception to active engagement with dynamic story-worlds, changing the artist-narrative-audience relationship.

Stories from Around the World: Global Perspectives

Narrative art is a universal human practice, but it shows up in incredibly diverse ways, shaped by the unique cultural, spiritual, and historical contexts of societies worldwide. Looking beyond the Western tradition reveals a rich tapestry of visual storytelling.

Beyond the West: A World of Storytelling

Japanese Emakimono Scrolls

Japanese emakimono, or illustrated handscrolls, are a sophisticated narrative art form from the Heian period (794-1185 CE).16 These scrolls, typically paper or silk, combine calligraphic text with painted scenes. They're unrolled horizontally from right to left, letting the viewer experience the story sequentially at their own pace.16

While rooted in China, Japanese artists adapted the handscroll format, introducing distinct themes, styles, and narrative conventions.16 Famous examples include the Genji Monogatari Emaki (early 12th century), a visual adaptation of "The Tale of Genji." This emaki exemplifies the onna-e ("women's pictures") style, focusing on Heian aristocrats' emotional lives. It uses techniques like tsukuri-e (built-up pictures), hikime kagihana (stylized facial features), and fukinuki yatai ("blown-off roof" perspective) to convey subtle emotional narratives.16

In contrast, the Choju-jinbutsu-giga ("Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans," 12th-13th centuries) is a celebrated example of the otoko-e ("men's pictures") style. These monochrome ink scrolls, often seen as a precursor to modern manga, depict animals behaving like humans in humorous and satirical scenes, possibly parodying contemporary society, without accompanying text.16 Emakimono not only tell stories but also reflect societal views, aesthetic preferences, and cultural shifts, offering invaluable insights into Japanese history and art.16

Mexican Codices (Pre-Columbian and Colonial)

Mesoamerican civilizations like the Aztec, Maya, and Mixtec developed sophisticated manuscript traditions known as codices long before European contact.17 These codices, usually made on long strips of bark paper (amate) or deerskin and folded accordion-style, were vital knowledge repositories. They recorded history, genealogies, tribute, religious rituals, astronomy, calendars, mythology, and divinatory practices.17

Narrative was conveyed through intricate pictorial systems, often with glyphs, relying on specific spatial arrangements, color-coding, and directional cues to ensure narrative continuity and convey complex meanings.17 Interpreting them often required active engagement and specialized knowledge.20

Notable examples include:

- Aztec Codices: Such as the Codex Borbonicus (ritual calendar), Codex Mendoza (history, tribute), and Codex Borgia (divinatory).17

- Maya Codices: Fewer pre-Columbian examples survive, but the Dresden Codex, Madrid Codex, and Paris Codex are crucial for understanding Maya astronomy, calendars, and religion.17

- Mixtec Codices: Known for detailed historical and genealogical narratives (e.g., Codex Zouche-Nuttall, Codex Selden).17

After the Spanish conquest, codex creation continued for a time, but often with European influences in style, materials, and content, resulting in colonial-era codices blending indigenous and European traditions.17 These surviving manuscripts are invaluable for understanding pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

African Storytelling Textiles

Across Africa, textiles have long been powerful mediums for storytelling, historical documentation, and cultural expression.18 More than just decorations, these fabrics often embody intricate narratives, commemorate events, convey social status, and play central roles in ceremonies.18

- Kuba Cloth (Democratic Republic of Congo): Kuba peoples are renowned for elaborate raffia textiles. Woven from palm fibers, these cloths were linked to royalty and used ceremonially.18 Intricate geometric patterns, called buina, often have names referring to rhythm and movement.87 Their creation is a communal effort, and the raffia itself holds symbolic value.87 Kuba cloths are vital in rituals, especially funerals.87

- Kente Cloth (Ashanti, Ghana): One of the most famous African textiles, Kente is a complex strip-woven cloth traditionally made by men for Ashanti royalty and worn during important ceremonies.18 Vibrant colors and geometric patterns often carry specific symbolic meanings.

- Adire Cloth (Yoruba, Nigeria): This indigo-dyed cloth is created by Yoruba women using resist-dyeing techniques to produce intricate patterns.18

- Bògòlanfini (Mud Cloth, Mali): Men weave cotton cloth which is then dyed using fermented mud, bark, and leaves to create symbolic designs.18

Contemporary African artists like El Anatsui and Wangechi Mutu often draw inspiration from these rich textile traditions, blending heritage with modern visual languages to create compelling narratives about identity, history, and social issues.86

Indigenous Storytelling Traditions (Australia, North America)

Indigenous cultures worldwide have rich, ancient traditions of visual storytelling, where art is deeply linked to land, spirituality, and ancestral knowledge.

-

Australian Aboriginal Art: This is one of the oldest continuous art traditions, with knowledge conveyed through stories, songs, dances, and visual art.19

- The Dreaming (or Dreamtime): The foundational concept in Aboriginal belief systems, referring to the ancestral creation epoch.19 Aboriginal artworks are visual manifestations of Dreaming stories, using symbols (dots, lines, circles) to represent ancestral journeys (Songlines), sacred sites, and natural elements.21 These narratives teach about landscape, morality, and social responsibilities.19 Story ownership is strictly governed by kinship.21

- Contemporary Dot Painting: While rooted in ancient practices, contemporary dot painting gained prominence in the 1970s with Papunya Tula artists.21 Using acrylics on canvas, artists translate sacred Dreaming narratives into permanent forms, often veiling secret-sacred information.21 Aerial perspectives are common.21 Notable artists include Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri.89

- Native American Narrative Art: As mentioned earlier, Plains Native American ledger art is a significant narrative tradition, evolving from hide paintings to works on paper documenting history and cultural experiences.61 Other Native American cultures also have rich narrative traditions in pottery, weaving, carving, and basketry, where symbols convey stories and myths.

Pre-Columbian Art (Mesoamerica and Andes - Maya, Moche)

Beyond codices, other Pre-Columbian art forms in Mesoamerica and the Andes also had strong narrative elements.

-

Moche Art (Peru, c. 100-800 CE): The Moche civilization is known for highly realistic figural imagery in murals, metalwork, and especially ceramics.91 Moche pottery features detailed depictions of rulers, warriors, priests, deities, and animals, often in complex narrative scenes that recur across vessels, suggesting standardized themes like hunts, sacrifice ceremonies, and battles.92 These ceramics likely served in daily rituals and as funerary offerings.92

- Maya Art: The Maya produced rich narrative art on stelae, lintels, murals, and ceramics.94 Their sophisticated writing system often accompanied images, providing details of historical events, royal lineages, and rituals.94 Famous examples like Lintel 24 from Yaxchilán vividly depict complex ceremonies like bloodletting.94

- General Pre-Columbian Narrative Elements: Across Mesoamerica, shared narrative elements included rebus writing systems, depictions of important deities (Tlaloc, Quetzalcoatl), cosmological diagrams, and symbolic representations of the ritual ballgame.94

Culture's Imprint: How Traditions Shape Stories

The content, form, and function of narrative art are deeply intertwined with the cultural values, beliefs, storytelling conventions, and material realities of the society that creates it. How "readable" these visual narratives are often depends heavily on the viewer's cultural literacy. What tells a clear story to an insider might be confusing or misunderstood by an outsider lacking the specific cultural codes and symbolic understandings.

For instance, in Japan, the Heian period's aristocratic focus on courtly romance and refined sensibilities is clearly reflected in the onna-e style of the Genji Monogatari Emaki. The intimate handscroll format itself aligns with this culture of private experience.16 The later, more satirical otoko-e style, seen in scrolls like the Choju-giga, signaled a cultural shift.16

Similarly, Mesoamerican codices required familiarity with complex calendrical systems and deity attributes.20 Aztec codices often emphasize history and tribute; Maya codices focus on astronomy and prophecy; and Mixtec codices detail royal genealogies.17 The visual language was highly codified and culturally specific.

In Australian Aboriginal culture, the Dreaming is the paramount spiritual framework informing all narrative art.19 Art is intrinsically linked to land, ancestral beings, and sacred laws. The symbols used are part of a complex system of meaning, and the right to depict certain stories is often restricted.21 An outsider might appreciate the aesthetics but miss the deep narrative and spiritual meaning without cultural context.

Furthermore, the very materials and techniques used are often intertwined with the cultural environment, reflecting available resources and symbolic associations. The use of raffia in Kuba textiles is a prime example; raffia is abundant locally and historically used as currency, imbuing the cloth with layers of meaning.87 Japanese emakimono adapted Chinese silk and paper scroll traditions.16 Mesoamerican codices used local bark paper or deerskin.17 This shows a practical and often symbolic relationship between a society's material culture and its narrative expressions, where the medium itself can be part of the message.

The Storyteller's Toolkit: Techniques, Media, and Forms

Artists wield a sophisticated array of visual strategies, devices, and conventions to build narratives, guide our interpretation, and stir our emotions. These techniques are adapted across countless media, each with its own unique storytelling strengths and limitations.

Crafting the Scene: Visual Strategies and Devices

Composition

Composition, how elements are arranged in an artwork, is fundamental to visual storytelling. Artists strategically place figures and objects and use space to direct our gaze (learn more about these in the guide to Art Fundamentals), imply sequence or importance, and set the mood.4 Common strategies include creating clear focal points, using the figure/ground relationship for depth, and applying principles like the rule of thirds for dynamic arrangements.97 Historically, religious art often used central symmetrical compositions for formality and solemnity.98

Sequential Imagery & Pacing

Showing a sequence of events is a hallmark of many narrative art forms, controlling the story's flow and building suspense or emotion.2 This sequence can be explicit, as in the panels and gutters of comics, which clearly mark distinct moments.99 Or, it can be implied within a single frame through arrangements suggesting past, present, and future actions.3 The narrative's pacing, how quickly information is revealed, can be manipulated by detail density, compositional complexity, or spatial framing, as seen in some Italian Renaissance paintings.101

Symbolism & Iconography

Symbolism and iconography are vital tools for conveying meaning, using objects, figures, colors, and gestures to represent ideas (understanding color theory can reveal deeper symbolic meanings) with culturally embedded significance.4 Symbolism uses images or signs with shared meaning (e.g., a rose for love).22 Iconography is the broader study of subject matter and themes, including implied meanings and symbols conveying shared history or myths.22 For example, a snake with Adam and Eve symbolizes temptation in Christian art, but might mean wisdom elsewhere.22

The meaning of symbols can change significantly across cultures and time.22 This means a viewer's familiarity with these visual codes affects how accessible and layered a narrative artwork is. Some symbols are widely recognized, while many are deeply embedded in specific cultural lexicons. For instance, the complex symbolism in Australian Aboriginal art is intrinsically linked to specific Dreaming narratives.21 Similarly, Roland Barthes' analysis of a Panzani ad shows how everyday objects become culturally charged symbols, connoting "Italianicity."29

Character & Emotion

Visually developing characters and effectively conveying their emotions are vital for engaging the audience.4 Artists achieve this through character design (appearance, costume), body language, facial expressions, and gestures. Color psychology, brushwork, and composition also contribute to the emotional tone and portrayal of a character's inner state.37 For example, late 19th-century Symbolist painters used suggestive imagery and non-literal color to evoke feelings.36

Depiction of Time & Space

Narrative art inherently deals with representing time and space, as stories unfold sequentially in specific settings. Artists have developed many conventions to depict these elements.2

Different modes of narrative time include:

- Monoscenic narrative: Depicts a single, crucial moment (e.g., Exekias's Achilles kills Penthesilea).2

- Continuous narrative: Illustrates multiple scenes in one visual field, often repeating the main character (e.g., Trajan’s Column).2

- Synoptic narrative: Presents a single scene with a character shown multiple times to convey various actions, sequence often unclear without prior story knowledge.2

- Cyclic or Sequential narrative: Figures repeated in distinct, often framed, scenes in chronological order, like a comic book.2

- Panoramic (or Panoptic) narrative: Depicts multiple scenes and actions, often simultaneous, without necessarily repeating characters.2

- Progressive narrative: A single scene where characters aren't repeated, but multiple actions convey time passage.2

- Serial narratives: Composite formats like polyptychs, where auxiliary panels expand the narrative.101

- Episodic contemplation: Multiepisodic artworks for meditative viewing, processing scenes sequentially.101

- Nonlinear narrative paths: Experimental storytelling disrupting chronological order (e.g., flashbacks).101

The choice of narrative mode profoundly affects how we experience and reconstruct the story. Continuous and synoptic narratives, for example, often demand more active mental engagement than explicitly structured sequential narratives.

Spatial representation is equally critical. Techniques like linear and aerial perspective, using architecture or landscape as spatial framing aids, and manipulating foreground/background relationships create depth, establish settings, and guide us through the narrative space.4 The field of visual narratology studies these aspects, examining how time, motion, and viewer perception contribute to storytelling in images.105 Scholars like Variji and Dadashi argue that even static images effectively represent narrative time, challenging theories privileging linguistic narratives.105

Setting & Atmosphere

The setting, the specific time and place of the story, and the overall atmosphere contribute significantly to storytelling.4 Artists use landscape, architecture, lighting, color palettes, and weather to establish a convincing environment and evoke a mood that complements the narrative.107 A well-crafted atmosphere can transport viewers, enhancing their emotional connection.107 For example, a dark, shadowy setting might create suspense, while a bright, sunlit scene could convey joy. (explore the importance of the background in art here)

Text Integration

Integrating text with visuals is common in many narrative art forms.3 Text can be captions, dialogue (speech bubbles), inscriptions, or extensive passages with illustrations. Roland Barthes, in "Rhetoric of the Image," identified two main functions of text with images: anchorage and relay.29

Anchorage occurs when text limits an image's potential meanings, guiding interpretation (common in news or ads). Relay describes a complementary relationship where text and image work together, each contributing unique information (characteristic of comics).29 Barthes also argued that a photograph's literal message often naturalizes its symbolic message.29 The relationship between text and image is often mutually reinforcing, but can also involve tension, as text often attempts to control the interpretation of more open-ended images.

From Canvas to Code: Narrative Across Media

Narrative art appears across a vast spectrum of media, each with unique characteristics shaping how stories are told and experienced. The choice of medium isn't just technical; it's integral to the narrative expression, influencing aesthetics, detail, dissemination, and viewer engagement.

Painting, Sculpture (Reliefs, Installations), Tapestry, Manuscript Illumination, Printmaking

These traditional media have been foundational for centuries.

- Painting has dominated storytelling, from ancient murals to contemporary canvases, offering rich visual narration within a single frame or series.

- Sculpture, especially relief sculpture, has a long narrative history (e.g., Egyptian tombs, Roman columns, medieval cathedrals).12 Modern installation art can transform spaces into immersive narrative environments.111

- Tapestry and other textiles have been significant narrative vehicles (e.g., Bayeux Tapestry,2 African storytelling cloths18).

- Manuscript Illumination was the primary book-based narrative art before print (e.g., European codices, Japanese emakimono,14 Mesoamerican codices).

- Printmaking (woodcut, engraving) allowed wider dissemination of narrative images from the Renaissance onward (e.g., Dürer, Goya115).

Photography, Comics, Graphic Novels, Storyboards

Mechanical and photographic reproduction opened new avenues for narrative art.

- Photography developed narrative capacities beyond documentation, used for documentary storytelling (e.g., Brady, Lange), staged narratives (e.g., Crewdson), photographic sequences (e.g., Muybridge), and photo essays (e.g., Frank's The Americans).74

- Comics and Graphic Novels are a distinct narrative art form with sequential juxtaposed images and text, telling diverse stories from superhero adventures to complex autobiographies.69

- Storyboards are sequential drawings planning film or TV shots, crucial for visualizing narrative flow.

Animation, Film, Video Art

Time-based media introduced dynamic movement and sound.

- Animation evolved from hand-drawn experiments to sophisticated CGI, telling complex, feature-length stories.75 Experimental animation also explored non-narrative visual experiences.75

- Film (live-action cinema) developed its own narrative language. Pioneers like D.W. Griffith introduced techniques like close-ups and editing.77 Soviet filmmakers like Eisenstein explored montage for symbolic meaning.78 Visual storytelling in film uses cinematography, lighting, design, sound, and editing.79

- Video Art, emerging in the 1960s (e.g., Nam June Paik, Bill Viola), uses video technology, often exploring non-linear narratives and interactivity.117 Multi-channel installations can create complex, layered narratives.117

Digital Art, Interactive Storytelling, AR/VR, Multimedia Narratives

The digital revolution profoundly expanded narrative art's possibilities.

- Digital Storytelling encompasses narratives created with digital tools, often multimodal (text, image, audio, video, interactive elements), non-linear, and participatory.23 Platforms include websites, social media (Instagram Stories, TikTok), blogs, and apps.23

- Interactive Narrative involves audience participation influencing the story (prominent in video games, interactive websites).24 Tools like Twine and game engines (Unity) facilitate complex branching narratives.24 Balancing agency with coherence is a key challenge.80

- Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are increasingly integrated for immersive, interactive experiences.31 VR places viewers in story-worlds; AR overlays narratives onto physical environments (e.g., Artivive app31). AI can assist in creation or adapt narratives in real-time, personalizing experiences.31 Artists like Refik Anadol and collectives like TeamLab explore these frontiers.31

Installation and Performance Art Narratives

These contemporary forms often incorporate narrative experientially.

- Installation Art creates immersive environments where narrative unfolds spatially, through objects, atmosphere, and media integration.111 It often invites interaction (e.g., Ilya Kabakov's The Man Who Flew into Space...).111

- Performance Art involves live actions, often telling stories through action, gesture, and context.122 It frequently addresses social, political, or personal themes, with narrative emerging from the live experience (e.g., Yoko Ono's Cut Piece).123

The chosen medium actively shapes storytelling possibilities, viewer engagement, and the type of narrative conveyed. Static media rely on implied sequences; sequential media make timelines explicit. Time-based media control pacing dynamically. Interactive digital media introduce viewer agency, allowing co-creation.

Table: Comparison of Narrative Capabilities Across Select Media

| Medium | Key Narrative Strengths | Limitations for Narrative | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Painting (Single Frame) | Evocative power, rich symbolism, depiction of "pregnant moment," implied sequence, emotional depth. | Primarily static, relies heavily on viewer inference for sequence and causality, limited direct temporal unfolding. | Giotto's frescoes 15 , Vermeer's The Milkmaid 5 , Norman Rockwell's covers. 25 |

| Relief Sculpture | Durability, public display, can depict extended sequences (continuous friezes), tangible presence. | Static, often requires specific viewing paths for continuous narratives, detail can be limited by material. | Trajan’s Column 2 , Ancient Egyptian tomb reliefs 12 , Ara Pacis. 13 |

| Illuminated Manuscript | Integration of text and image, sequential page-turning, detailed miniatures, portability (for codices). | Labor-intensive, limited audience before printing, fixed sequence. | Book of Kells 55 , Genji Monogatari Emaki . 16 |

| Comics/Graphic Novels | Explicit sequentiality (panels, gutters), direct integration of text (dialogue, narration), control over pacing. | Can be perceived as less "serious" than other art forms (though this is changing), visual style can limit realism if desired. | Maus (Spiegelman) 69 , Watchmen (Moore/Gibbons) 69 , Persepolis (Satrapi). 71 |

| Photography (Single) | Captures specific moments with realism or staged intent, powerful emotional impact, can imply broader context. | Static, meaning often reliant on captions or viewer knowledge to construct a full narrative. | Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother 74 , Gregory Crewdson's staged photos. 116 |

| Film/Animation | Dynamic movement, controlled pacing and time, sound (dialogue, music, effects), immersive visual experience. | Can be expensive to produce, often requires collaborative effort, linear by default (though can be experimental). | Disney's Snow White 76 , Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin . 78 |

| Video Art | Exploration of non-linear narratives, interactivity, multi-channel presentations, deconstruction of traditional forms. | Can be less accessible than mainstream film, interpretation may be challenging. | Nam June Paik's works 117 , Bill Viola's installations. 117 |

| Digital/Interactive Art (incl. VR/AR) | High viewer agency, branching narratives, immersive environments, multimodal experiences, personalization. | Technological barriers (access, cost), potential for narrative incoherence if agency is too broad, evolving conventions. | Her Story (video game) 24 , AR art apps like Artivive 31 , VR experiences. |

| Installation Art | Immersive, multi-sensory, spatial storytelling, viewer movement can be part of narrative unfolding. | Site-specific, often temporary, can be physically demanding for viewer, narrative can be abstract or elusive. | Ilya Kabakov's The Man Who Flew into Space... 111 , Ann Hamilton's the event of a thread . 111 |

| Performance Art | Live, direct engagement, embodied storytelling, often addresses immediate social/political issues. | Ephemeral (though documented), interpretation heavily reliant on context and live experience, can be confrontational. | Yoko Ono's Cut Piece 123 , Chris Burden's Shoot . 123 |

Master Storytellers: Notable Examples and Artists

Throughout history and across cultures, countless artists and artworks have shaped our understanding of narrative art. Let's explore some key examples that showcase the breadth and depth of visual storytelling.

Ancient Echoes: Narratives from the Ancient World

-

Trajan’s Column (Rome, 113 CE, marble relief): This monumental column, likely designed by Apollodorus of Damascus, features a continuous spiral frieze meticulously narrating Emperor Trajan's victories in Dacia. It's a historical record and imperial propaganda, currently in Rome.2

- Greek Pottery (e.g., Achilles kills Penthesilea amphora by Exekias) (c. 540-530 BCE, black-figure ceramic): Ancient Greek vases are famed for narrative scenes. Exekias's amphora (British Museum, London) masterfully captures Achilles fatally wounding Amazon queen Penthesilea, their eyes meeting, a poignant monoscenic narrative.2

Medieval Chronicles: Stories in Thread and Ink

- Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1070s, embroidered cloth): This nearly 70-meter-long embroidery vividly recounts events leading to the 1066 Norman Conquest of England. Likely commissioned by Bishop Odo of Bayeux, it presents a continuous narrative with Latin inscriptions. Housed in Bayeux Museum, France, it's a crucial historical document.2

- Illuminated Manuscripts (e.g., Lindisfarne Gospels, Book of Kells): These handwritten books are famed for lavish decoration, including narrative miniatures illustrating biblical or secular tales. The Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library) and Book of Kells (Trinity College, Dublin) are masterpieces of Insular art.14

Renaissance Reawakenings: Humanism in Narrative

- Giotto di Bondone, Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes (Padua, c. 1305, fresco): Giotto's extensive fresco cycle in Padua, Italy, depicts scenes from the Life of the Virgin and Christ. These works are revolutionary for their naturalism, emotional depth, and innovative use of perspective, marking a pivotal moment in narrative painting.15

-

Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel Ceiling (Vatican City, 1508-1512, fresco): One of Renaissance art's most iconic achievements, Michelangelo's ceiling narrates key Genesis scenes, like The Creation of Adam. The powerful figures and dynamic compositions convey epic grandeur.4

Baroque Drama: Emotion and Intensity

- Caravaggio, The Calling of St. Matthew (c. 1599-1600, oil on canvas): In Rome's Contarelli Chapel, this painting exemplifies Caravaggio's dramatic chiaroscuro, narrating Christ calling Matthew. Intense light/shadow and realistic figures create immediacy and psychological depth.46

Reflections of Change: 18th-19th Century Narratives

- William Hogarth, A Rake's Progress (c. 1732-1735, series of 8 paintings): This series (Sir John Soane's Museum, London) satirically chronicles Tom Rakewell's rise and fall. Hogarth's detailed scenes, rich with symbolism, narrate a cautionary tale.2

- Francisco Goya, The Third of May 1808 (1814, oil on canvas): In Madrid's Museo del Prado, this painting powerfully depicts the execution of Spanish civilians by Napoleon's soldiers. Goya's expressive brushwork and focus on terror make it an enduring anti-war statement.46

Modern Voices: Early 20th Century and Illustration

- Norman Rockwell (1894-1978): An American painter and illustrator, celebrated for detailed, often humorous, narrative covers for The Saturday Evening Post.

- After the Prom (1957, oil on canvas): Exemplifies Rockwell's ability to tell stories of adolescent romance and 1950s customs through subtle details.25

- The Problem We All Live With (1964, oil on canvas for LOOK): This iconic image of Ruby Bridges being escorted to integrate an all-white school is a powerful narrative on racial segregation and the Civil Rights Movement.124 Rockwell's work, now recognized for sophisticated narrative construction, reflected and critiqued American values.25

Contemporary Currents: Mid to Late 20th Century and Beyond

- Faith Ringgold (1930-2024): A pioneering African American artist renowned for her "story quilts" combining painting, quilting, and text.26

- Street Story Quilt (1985, mixed media; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): This triptych quilt narrates a young Black boy's family story in Harlem, addressing racism, poverty, and resilience through painted scenes and handwritten text.26 Ringgold elevated craft traditions to tell powerful stories about African American life.26

- Kara Walker (b. 1969): A contemporary American artist known for room-sized black cut-paper silhouette installations.4

- Her silhouettes depict disturbing scenes confronting American slavery's brutal history and legacy. Walker states her work "mimics the past, but it's all about the present," using exaggerated imagery to provoke viewers.27 The silhouette form, a historical craft, is subverted to explore power, degradation, and resistance.27 Both Ringgold and Walker use traditionally "feminine" or "craft" media for potent narratives on race, gender, and history, subverting art hierarchies.

Graphic Storytellers: The Rise of the Graphic Novel

The graphic novel has matured into a vital medium for complex narrative art.

- Art Spiegelman, Maus (1980-1991): This groundbreaking, Pulitzer Prize-winning work recounts Spiegelman's father's Holocaust experiences, depicting Jews as mice and Germans as cats. It layers historical trauma with the complex father-son relationship.69

- Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis (2000-2003): An autobiographical graphic novel series about Satrapi's childhood in Iran during and after the Islamic Revolution. Its striking black-and-white style blends personal experiences with broader events.71

- Chris Ware (e.g., Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth, 2000): Acclaimed for formally innovative graphic novels. Jimmy Corrigan explores loneliness and family dysfunction through intricate layouts and a melancholic narrative.72

New Frontiers: Artists Embracing New Media

Contemporary narrative art increasingly uses digital and interactive technologies.

- Digital Storytellers: Many leverage social media (Instagram, TikTok) for short-form, visually driven narratives, often incorporating user participation.118

- Interactive Narrative Artists: Video games like Her Story (players piece together a crime narrative) and The Stanley Parable (subverts game narratives through choice) exemplify interactive digital narratives.24

- VR/AR Artists: Refik Anadol creates immersive data sculptures. TeamLab designs interactive digital art installations. AR apps like Artivive add animated narrative layers to physical artworks.31 These artists push boundaries, making viewers active participants or co-creators.

Why It Matters: Functions, Impact, and How We Understand Narrative Art

Narrative art plays many roles in societies, deeply affecting cultural understanding and individual perception. How we interpret it is a complex process, shaped by the art, the viewer, and the context.

Art's Role in Society: Cultural and Social Functions

Throughout history, narrative art has fulfilled vital roles:

- Storytelling: Its most fundamental function, preserving and transmitting cultural narratives, myths, and history.3

- Religious Instruction and Devotion: Visualizing sacred texts, teaching moral lessons, and inspiring faith (e.g., medieval stained glass, Renaissance frescoes).3

- Moral Lessons: Conveying ethical principles and societal values (e.g., Hogarth's series, Aboriginal Dreamtime stories19).

- Propaganda and Power: Glorifying rulers, commemorating victories, and asserting ideological dominance (e.g., Roman reliefs13).

- Commemoration: Remembering significant events and individuals.6

- Identity Formation: Shaping individual, communal, and national identities by articulating shared histories and values.4

- Social Critique and Activism: Challenging norms, exposing injustice, and advocating for change (e.g., Goya, Faith Ringgold, Kara Walker3).

- Entertainment: Providing pleasure and escape (e.g., historical epics, modern comics99).

- Personal Expression: Allowing artists to communicate unique experiences and ideas.3

These functions often overlap. A Renaissance altarpiece, for example, could narrate a sacred story, showcase patronage, reflect artistic skill, and reinforce cultural values simultaneously.15 Ancient Egyptian tomb art aimed to ensure passage to the afterlife while also recording status.12 This multifunctionality is a hallmark of narrative art.

The Viewer's Eye: Audience and Interpretation

The meaning we find in narrative art isn't just in the artwork itself; it's actively built through an interaction between the work, the viewer, and the viewing context.

How Viewers "Read" Narrative Art

We "read" narrative art by interpreting visual cues: setting, characters, expressions, actions, symbols, and composition.3 This process is deeply influenced by our own cultural context, personal experiences, knowledge, and familiarity with artistic conventions.3 An image easily understood by one group might be enigmatic to another lacking relevant "visual literacy."

Reader-Response Theory

Reader-response criticism, extended to visual arts, emphasizes the viewer's active role in creating meaning.131 The artwork isn't static; meaning is generated in the transaction between the work and the individual viewer, who brings their unique background and interpretive strategies.131 Concepts like Stanley Fish's "interpretive communities" (groups sharing reading styles) and Wolfgang Iser's "implied reader" (the ideal recipient an artwork seems to address) explain how interpretations can be both personal and socially conditioned.131 This theory validates multiple legitimate interpretations.

Art Historical/Critical Analysis

Art historians and critics use various methods to analyze narrative art:

- Pre-iconographic Description: What do you literally see? (Figures, objects, events)

- Iconographic Analysis: What do these elements conventionally mean? (Symbols, themes based on cultural/literary knowledge)

- Iconological Interpretation: What deeper cultural or historical meaning does the work reveal?

-

Erwin Panofsky's Iconology: A three-level method for interpreting art.28

- Pre-iconographic Description: Identifying primary subject matter (basic visual elements).

- Iconographic Analysis: Secondary meaning of images, themes, allegories (requires familiarity with sources, traditions).

- Iconological Interpretation: Intrinsic meaning as a symptom of cultural attitudes (connects art to broader contexts).

-

Roland Barthes' Semiotics: Applied semiotic theory to images.29 He identified three messages:

- The Linguistic Message: Accompanying text (captions). Text can anchor (limit image meaning) or relay (work with image to advance narrative).29

- The Coded Iconic Message (Connoted Image): Symbolic meaning from visual elements based on cultural codes (e.g., Panzani ad connoting "Italianicity").

- The Non-coded Iconic Message (Denoted Image): Literal identification of what's depicted. Barthes suggested the denoted image "naturalizes" the connoted message.29 Furthermore, Barthes' "Death of the Author" posits meaning lies with the viewer, not creator's intent.29

- Visual Narratology: Applies narrative theory to visual media, examining elements like story-discourse, narration mechanics, focalization, and time/causality representation.105

Interpreting narrative art is dynamic, shaped by the artwork's cues, the viewer's background, and prevailing interpretive frameworks.44 These frameworks also evolve, leading to new insights into past artworks.

The Ripple Effect: Broader Impact of Narrative Art

Narrative art's impact is profound. Culturally, it shapes collective memory by transmitting stories defining a group's heritage and identity.10 It can reinforce or critique cultural values, prompting reflection and change.10 By telling stories, art builds communities and fosters shared understanding.11

Socially, narrative art influences behavior and norms. It's been used for moral instruction, political persuasion, and activism.19 By depicting diverse experiences, especially of marginalized groups, it can foster empathy and dialogue.10

Psychologically, engaging with narrative art evokes emotions, stimulates imagination, and aids cognitive development.37 Visual storytelling engages brain regions for emotions and memories, fostering deeper connections.142 Narratives help individuals make sense of their lives and the world, contributing to identity and meaning-making.127 Research suggests narratives aid in simulating and anticipating future events.127 The coherence from personal and cultural narratives is crucial for well-being.127

Narrative Art Today and Tomorrow: Relevance and Future Paths

Narrative art is a vibrant, ever-evolving field, constantly adapting to new cultural landscapes, artistic innovations, and technological leaps. Contemporary artists are reinterpreting old forms and finding novel ways to tell stories that connect with modern audiences.

What's Happening Now: Modern Practices and Trends

Contemporary narrative art (roughly 2015-2025) is diverse and deeply engaged with pressing social, political, and personal themes. Key trends include:

- Focus on Marginalized Voices: A significant shift towards foregrounding narratives historically underrepresented, stories of identity, migration, decolonization, and ecological urgency. This creates a "kaleidoscope of interconnected stories"30 and greater representation for female artists, artists of color, Indigenous artists, and LGBTQ+ artists.30

- Return to Materiality and Craft: Alongside digital media, many artists embrace handmade, tactile practices. There's a resurgence in traditional techniques like fiber/textiles and ceramics, imbued with contemporary meaning.30 Artists like Melissa Joseph and Sagarika Sundaram are redefining textiles for complex narratives.30 This trend often serves as a counterpoint to the digital age's intangibility.

- Exploration of Afrofuturism and Speculative Narratives: Afrofuturism (blending sci-fi, history, and fantasy to explore the African diaspora experience) remains significant.30 Lauren Halsey integrates architecture, community, and Afrofuturism.30 Speculative narratives tackling socioecological complexities and the climate crisis are also prominent.30

- Narrative-Driven Figurative Painting: Continued interest in figurative painting exploring cultural heritage, memory, and emotion. Artists like Alessandro Florio and Touils exemplify this,48 while Jessica Brilli taps into nostalgia,48 and Deborah Segun explores feminine power.48

These trends show a dynamic art scene where narrative is a critical tool for engaging with modern complexities, history, and identity. Telling stories from previously silenced perspectives becomes a cultural and political act.

The Digital Canvas: New Technologies and Media

New technologies are dramatically reshaping narrative art, offering unprecedented tools for creation, dissemination, and engagement.

- Digital Storytelling Platforms: Social media like Instagram and TikTok are major venues for short-form visual storytelling, often interactive.81 Websites, blogs, and apps also provide versatile platforms for multimedia narratives.23

- Interactive and Immersive Narratives: Interactivity is key. Video games, interactive websites, and digital installations allow audience choices to influence outcomes, making viewers active participants.24 Tools like Twine and game engines (Unity, Unreal) are widely used.24

-

Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), and Artificial Intelligence (AI): These push boundaries of immersion and interaction.31

- VR transports viewers into story-worlds.

- AR overlays digital narratives onto physical environments (e.g., Artivive app31).

- AI acts as a creative collaborator, generating visuals or adapting narratives in real-time based on viewer interaction.31 AI can personalize experiences and create evolving generative art. These technologies foster new, dynamic, responsive narrative forms, shifting the storyteller-story-audience relationship towards co-creation.

Talking Points: Current Debates and Emerging Trends

As narrative art evolves, important debates around accessibility and inclusivity are shaping its practice and reception.

- Accessibility: Museums are increasingly focused on making art accessible to diverse audiences, including physical (ramps, signage) and digital accessibility (accessible websites, virtual tours).128 For narrative art, this means considering communication for different sensory abilities (audio descriptions, tactile displays).128 Welcoming plaza designs with seating also improve visitor experience.147

- Inclusivity and Diverse Storytelling: A major trend is pushing for greater inclusivity in stories and artists represented.30 Museums are called to exhibit works reflecting broader cultural heritages and experiences, moving beyond traditionally Eurocentric narratives.30 This involves showcasing underrepresented artists and collaborating with community groups.128 The goal is an equitable art world where all voices are heard.128 Organizations like Queer|Art and NALAC support this.128

- Ethical Considerations in Digital Narratives: AI and digital tools raise ethical questions about authorship, authenticity, data privacy, and algorithmic bias.

- The Role of the Institution: Museums are seen as spaces for empathy and dialogue, where inclusive storytelling can be transformative.149 This requires a comprehensive approach to Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion (DEAI).149

These discussions highlight a growing awareness that narrative art's power lies in its ability to connect with diverse audiences meaningfully and equitably. The future will likely see continued exploration of these issues.

Learning Through Stories: Pedagogical Uses of Narrative Art

Narrative art is a powerful and versatile educational tool, fostering critical skills and deeper understanding across disciplines. Its visual and emotional engagement is particularly effective for developing visual literacy, critical thinking, storytelling abilities, empathy, and cultural awareness.

In the Classroom: Narrative Art for Teaching and Learning

Incorporating narrative art into curricula offers many benefits:

- Developing Visual Literacy: Crucial in a visual age, visual literacy is the ability to see, interpret, evaluate, and create meaning from images.32 Narrative art requires students to decode visual cues, understand symbols, and interpret how elements contribute to a story.6 Analyzing narrative construction helps students critically examine visual messages.32 This involves metacognition, reflecting on how they derive meaning.32